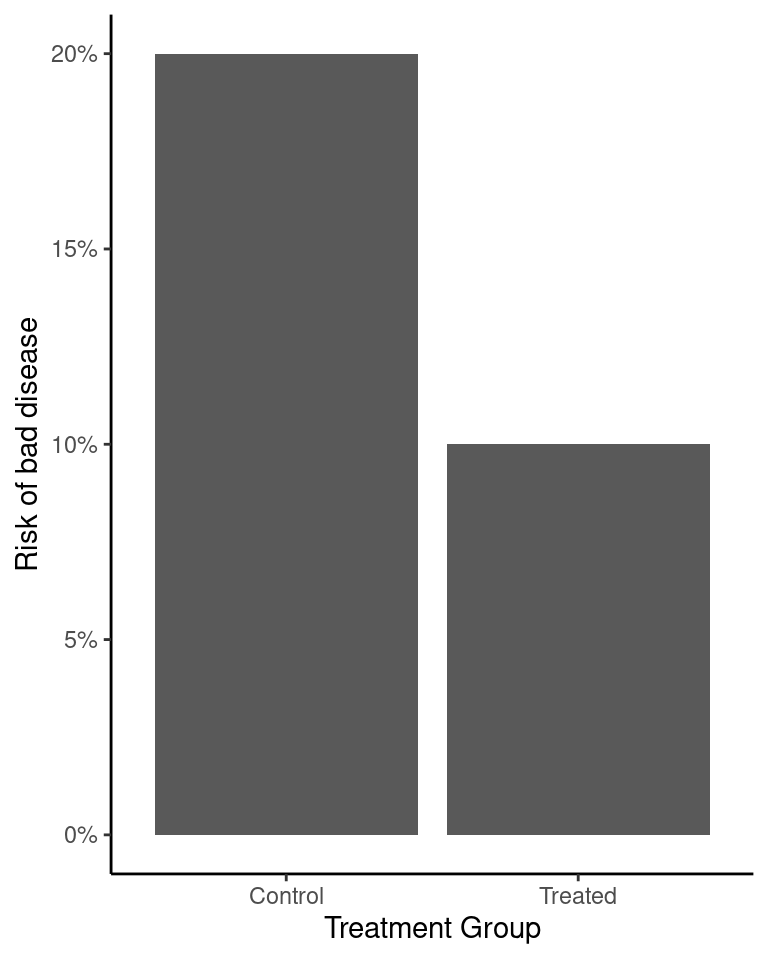

Usually, when evaluating an intervention, we look for a well-designed study that reports something like this:

This looks pretty good, because the risk of getting the disease among the treated group is only half the risk in the untreated group.

When talking about interventions, the vast majority of the conversation is about whether or not we can actually trust our estimate of the effect that the treatment had. We talk about the possibility that the difference arose due to random chance, confounding, or some other kind of bias, and how randomized controlled trials are ideal because they can protect us from some of these issues. We check for conflicts of interest and make sure we aren’t being misled. Once an intervention passes all these tests, people tend to feel comfortable recommending it.

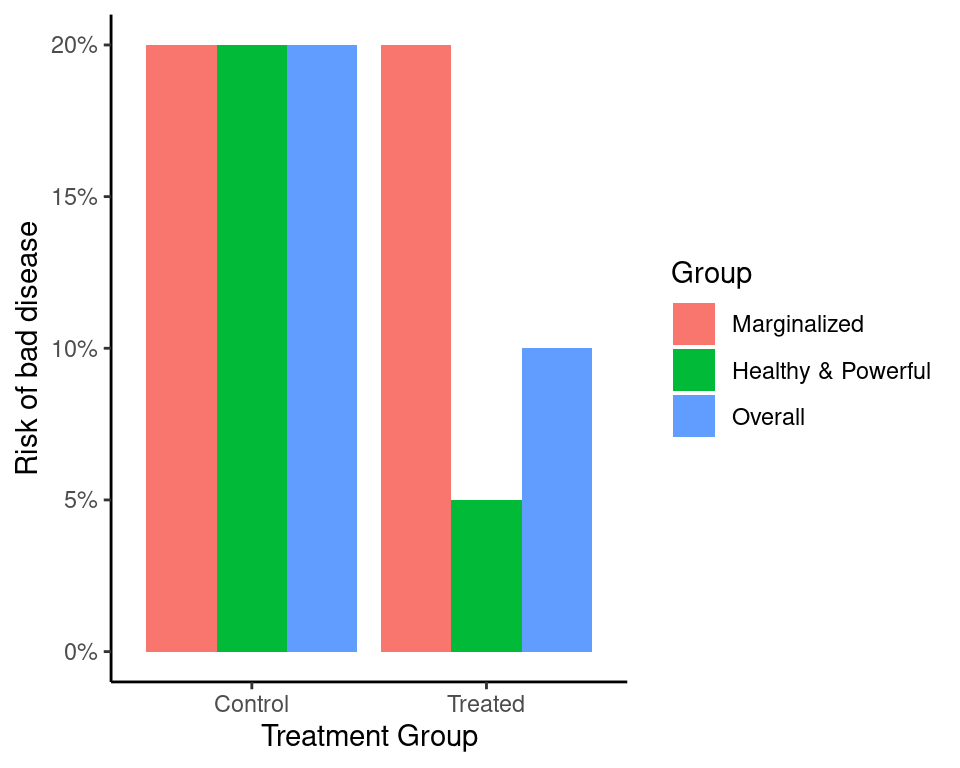

In lots of cases, though, we aren’t measuring the right thing. Here’s the problem:

Overall, things are better, but only because the healthier group gets healthier. The treatment’s main effect is to widen the gap.

If we don’t check for this, we can’t prevent it. Every paper in public health and medical research should do this kind of analysis so that the equity impact can be assessed.